LA: A 50th reunion

WHEN you’re young, it’s easier to dismiss setbacks and move on. LA, the weekly newspaper that gave me my first job as a publication art director, folded after 24 issues. It failed. But everyone there quickly found other things to do, and I don’t think any of us filed for unemployment. The failure marked my thinking about the work. I remembered the sloppy layouts, weak illustrations, poorly lighted photos, and bad printing—sometimes forgetting the good stuff.

Fifty years after the launch in July 1972, taking a look at the bound volume, I was struck by how good it actually was—the design and also the reporting and writing. The sloppy parts could be excused by the combination of mad experimentation, inexperience, and hurry. I started getting in touch with the surviving staffers and contributors. Some I’d worked with since and kept in touch with. Terry McDonell went on to work at Rolling Stone and Newsweek, although we didn’t overlap. He then brought me into Smart and then Esquire, and he was a great editor at both.

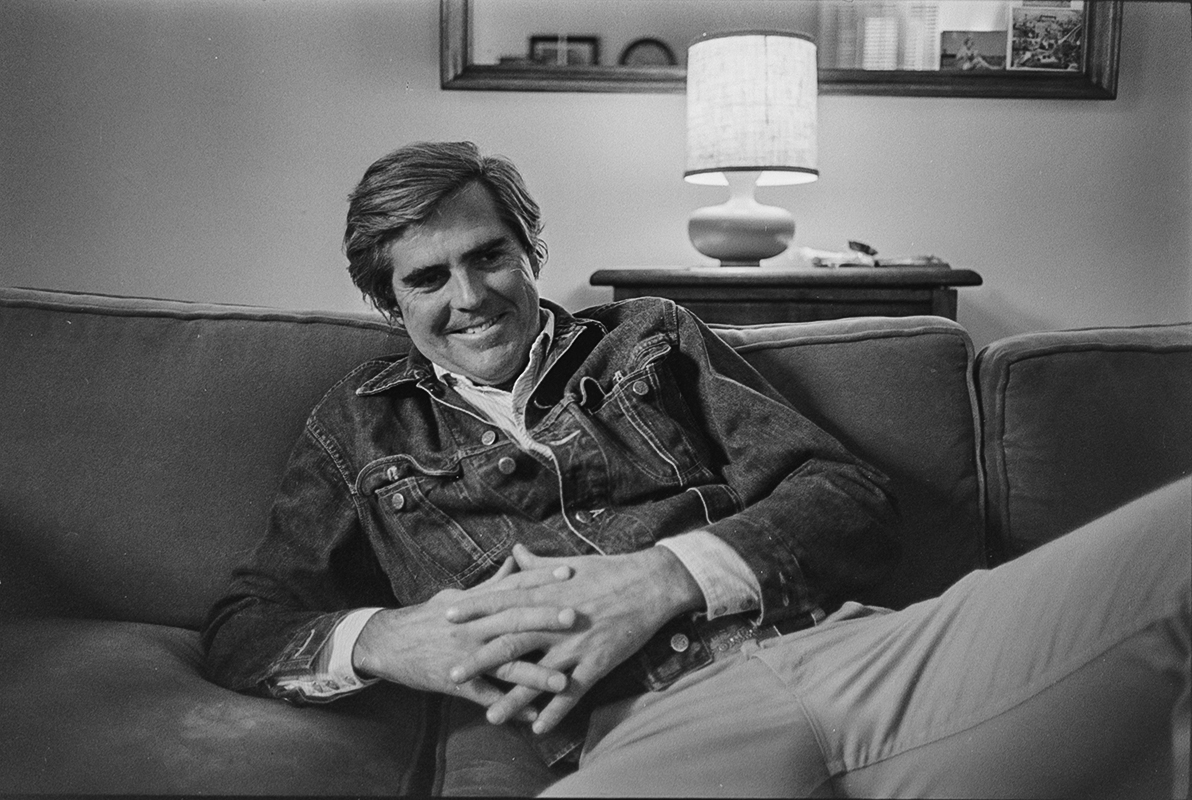

Staff reporter and photographer Terry McDonell, reporter Barry Siegel, photographer David Strick listen to Anne Taylor Fleming, reporter and editor of the “LA Guide” section, tell the story of the launch of the newspaper.

Over the years, I had seen David Strick, our staff photographer, as well as Tom Ingalls and Jim MacKenzie from the art department, later my partners in Type City. Strick was in touch David Barry, the rock critic, and with Barry Siegel, the reporter (later a winner of two Pulitzers at the Los Angeles Times). Barry gave me the email address of Anne Taylor Fleming, who has had a great career as writer, columnist and TV commentator. [More comments about these people can be found in my previous posts about LA.]

It seemed obvious to meet in person—to have a reunion. I’d helped organize a Rolling Stone reunion in 2017 for veterans of he first ten years of the magazine, before the move from San Francisco to New York. That event was like an acid flashback. So let’s do one for LA!

Anne Taylor Fleming, with artist Joan Nielsen, movie critic Stephen Farber, and music critic David Barry at the reunion.

Google Search made it easy to find media people who eventually went online. I located many LA staffers. John Fleischman, wrote the cover story in the first issue and is still writing, now from Cincinnati. Joan Nielsen, artist and designer who later turn to catering, responded quickly. Lanie Peterson (then Lanie Jones), a staff reporter, showed up on Linkedin; she has long been on the masthead at the Savannah Morning News. Stephen Farber, the movie critic, is still watching films and writing about them. Peter Green, the cartoonist, is in the LA area, still working, and still funny. Catherine Zogby-Bothum (now Catherine Lampton), the designer I hired to make our “pub-set” ads and later brought in at Cycle News, was tracked down in Hawaii where she has a whole new career (and a PhD) as a conflict mediator.

Lynn Lascaro, the artist known as Napoleon, is my Facebook friend. (He sent a masthead condor he drew for Karl Fleming to replace the LA-Love-It-or-Leave-It eagle, but I don’t think it ever ran.) Jan Harkus (now Jann Littleton) was the office manager who hooked up with my ex-brother-in-law, David Roberts, a columnist on the masthead, had a child together named Funn, and is still in touch with my nieces and their kids.

Almost everyone was able to go to the reunion in Los Angeles, or joined via the internet.

Not all of the LA staffers could be invited. David Roberts was one of the contributors who did not survive. He was 15 years older than most of us. The guys at the top-of-the-masthead, also older, had long lives, but have passed away: Karl Fleming, the founder and editor; Bob Sherrill, the managing editor; and Bill Cardoso, the senior editor. Max Palevsky, the zillionaire backer who dropped the newspaper the same year he funded it, died in 2012.

And there are other missing colleagues: Michael Parrish, who I brought in as production manager and later became editor of the Los Angeles Times Magazine; Perry Deane Young, a brilliant writer; Robert Blue, a frequent contributor of slick illustrations who became well-known for his pinup style paintings; and Scot Gaznier, the third editorial designer, who led the team in the ritual dancing whenever “Pico and Sepulveda” whenever came on the Dr. Demento show on KMET.

I could never find Judy Lewellen, the copy chief; the artist Brian Davis; the photographer Jed Wilcox; the great writers John Kaye and Tom Moran; reporter Janie Greenspun (now Jane Gale); or Paul Cheslaw who had been at Print Project Amerika and was the promotion manager at LA with the title, Minister of Propaganda.

But, during the weekend before Halloween, ten survivors met at David Stick’s house in West LA—and for several great meals outside (literally) including a dinner in Santa Monica at the beautiful garden of Michael’s, a classic 70s LA restaurant. Another seven joined via Google Meet.

The general conclusion was that LA was a great experiment, and much better than anyone remembered.

And why? Most credited Karl Fleming with a great eye for talent. This sounds self-serving, since we were the ones hired, but his choices all proved their talents later.

The staff quickly jelled into a team with energy and enthusiasm. We egged each other on.

Fleming and Sherrill, with their instincts and practiced judgement, kept handing out interesting assignments. They were triangulating The New Yorker, New York magazine, and the Village Voice. They wanted some hard news. They wanted service. But most of all they wanted good powers of observation and good writing. Cardoso was their Tom Wolfe, their Hunter S. Thompson, but everyone jumped in. Stories came in about (to name a few) the Crips, Tony and Susan Alamo, the Manson family, Coppola, Lassie, Monti Rock III, Mayor Yorty, abortions, Tim Leary, Oscar Levant, Leon Russell, a roller derby queen, Nixon, Terry Moore, the Queen Mary, Gram Parsons, Mose Allison, and, of course, Joan Didion. Plus book and rock music reviews, and a service section edited by Anne Taylor Fleming with items on the best food, shops, galleries, and events from the whole LA area—all brightly and briefly written.

Fleming and Sherrill line-edited every piece, but the key to getting so much good writing and reporting was a combination of high expectation, and great freedom, and raw talent. They assumed you were going to do a good job, and you tried as hard as you could.

This was especially true for the design. My only experience as a manager in a publication was confined to a year as editor of a college newspaper (The Chicago Maroon) in 1968, the one-issue run of Print Project Amerika in 1970, and five issues of the Mayday newspaper in 1971. But my experience was as an editor, not an art director.

Karl Fleming assumed I knew what I was doing, or else he was too busy doing everything else. Reporters from his generation didn’t have to think much about layout. News organizations were specialized. But he did know photojournalism, and took many LA pictures himself, including a strong cover shot of an Arlington funeral for a story timed for Veterans Day.

McDonell came to LA from the Associated Press where he had been a photographer and news cameraman in Iran. In the first issues of the filler he filled columns with as pictures as well as text. In No. 1 he took the striking photos of the reformed gang members in the story, “The Baddest.” McDonell was, like all of us, forming his ideas of what he wanted to do. In his case he set his sites on becoming an editor, and he did. He knew that knowing how to combine written content with visual content that makes a good editor.

Fleming wanted both, and he didn’t really care how it he got it. He did not set up a traditonal, hierarchical newsroom. He didn’t ask where every idea came from, but challenged them most of them until he and Sherrill got the answer to his question, “What’s the point?”

In the 60s there was an idea that publications could be organized as collectives. This did not work for me at the Mayday project, but I liked the spirit of collaboration among equals, even if it meant a lot of arguments. Two heads are better than one. All I knew about the layered specialization of newsrooms was what I learned as a summer intern of the Houston Post, and I didn’t like it. Instead of a separate production group the three designers in the art department did their own pasteup from their own layouts. Sometimes, they could work from a half-size sketch that we agreed on, and sometimes they just waded into the final pasteups.

We were thinking about making a newspaper that was more like a magazine. The first thing was to make the issue a series of spreads. Stories could run from page to page without newspaper jump lines (“Continued on page 12”). The layout was done in units of columns, and the ads were stacked vertically. I tried running headlines over the gutter to tie a story together—which never worked.

The copy was so late every week that we didn’t have much time to argue about the layouts. The only big fight I had with Karl Fleming was over the size of the logo. (I lost.) But Fleming kept on me about the content of the design, and encouraged everyone in the art department to take pictures.

David Strick, a Cal Arts student, had come in for one early assignment. Strick recalled at the reunion that I held a shape-up for the early issues, where a bunch of photographers would come to office, and I’d hand out assignments. Fleming liked his take, and wanted to interview Strick. He hired him on the spot, and when he found out he was living at home, he offered $75 a week, and Strick took it!

Through the Cal Arts connection LA developed a relationship to photographers, who were street photographers in the style of Robert Frank. There was Peter Karnig (who couldn’t attend the reunion) and Jed Wilcox. Their pictures hold up over time.

And that’s the difference looking at LA today. Much of it holds up beautifully. Some stories—and art and design—fell flat. But, hey, we’ll get it right next week!

The group photo at the end of the reunion at David Strick’s house in West LA. Front row: Joan Nielsen, David Strick, Anne Taylor Fleming. Back row: David Barry, Terry McDonell, Stephen Farber, Tom Ingalls, Barry Seigel, Roger Black. [Photo: Gabriel Strick]